SOURCE: Iain Davis and Whitney Webb via Unlimited Hangout

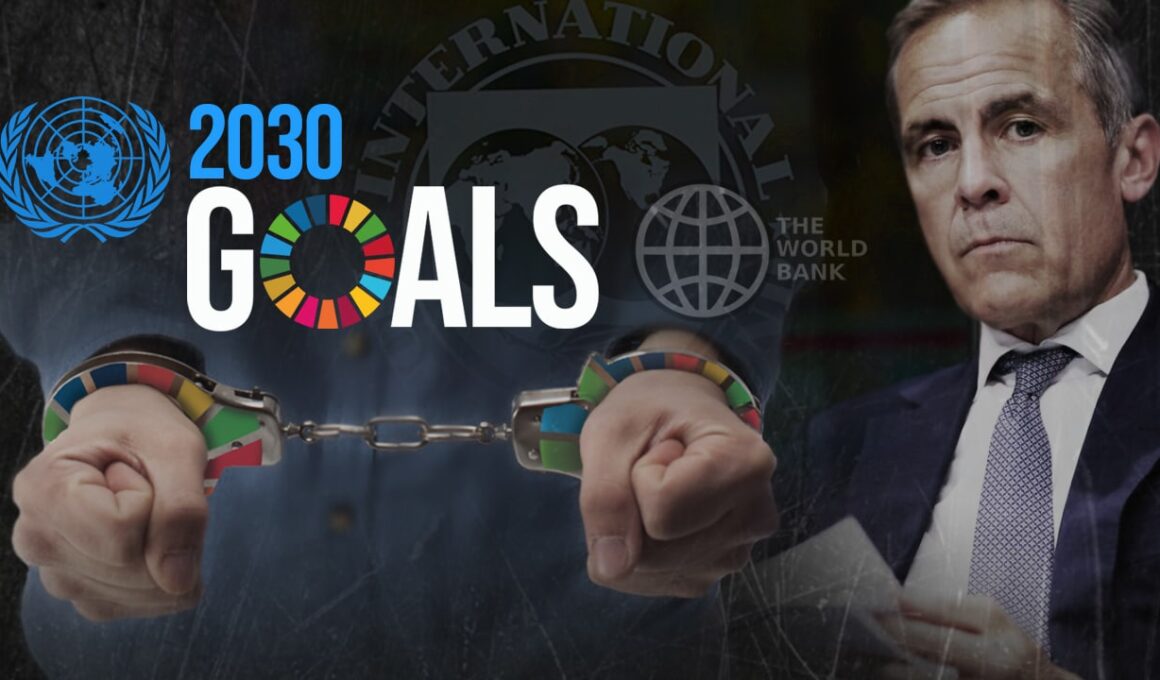

In this first instalment of a new series, Iain Davis and Whitney Webb explore how the UN’s “sustainable development” policies, the SDGs, do not promote “sustainability” as most conceive of it and instead utilise the same debt imperialism long used by the Anglo-American Empire to entrap nations in a new, equally predatory system of global financial governance.

The UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is pitched as a “shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future.” At the heart of this agenda are the 17 Sustainable Development Goals, or SDGs.

Many of these goals sound nice in theory and paint a picture of an emergent global utopia – such as no poverty, no world hunger and reduced inequality. Yet, as is true with so much, the reality behind most – if not all – of the SDGs are policies cloaked in the language of utopia that – in practice – will only benefit the economic elite and entrench their power.

This can clearly be seen in fine print of the SDGs, as there is considerable emphasis on debt and on entrapping nation states (especially developing states) in debt as a means of forcing adoption of SDG-related policies. It is then little coincidence that many of the driving forces behind SDG-related policies, at the UN and elsewhere, are career bankers. Former executives at some of the most predatory financial institutions in the history of the world, from Goldman Sachs to Bank of America to Deutsche Bank, are among the top proponents and developers of SDG-related policies.

Are their interests truly aligned with “sustainable development” and improving the state of the world for regular people, as they now claim? Or do their interests lie where they always have, in a profit-driven economic model based on debt slavery and outright theft?

In this Unlimited Hangout investigative series, we will be exploring these questions and interrogating – not only the power structures behind the SDGs and related policies – but also their practical impacts.

In this first instalment, we will explore what actually underpins the majority of the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs, cutting through the flowery language to deliver the full picture of what the implementation of these policies means for the average person. Subsequent instalments will focus on case studies based on specific SDGs and their sector-specific impacts.

Overall, this series will offer a fact-based and objective look at how the motivation behind the SDGs and Agenda 2030 is about retooling the same economic imperialism used by the Anglo-American Empire in the post-World War II era for the purposes of the coming “multipolar world order” and efforts to enact a global neo-feudal model, perhaps best summarized as a model for “sustainable slavery.”

The SDG Word Salad

Most people are aware of the concept of “Sustainable Development” but, it is fair to say that the majority believe that SDGs are related to tackling problems allegedly wrought by climate disaster. However, the Agenda 2030 SDGs encompass every facet of our lives and only one, SDG 13, deals explicitly with climate.

From economic and food security to education, employment and all business activity; name any sphere of human activity, including the most personal, and there is an associated SDG designed to “transform” it. Yet, it is the SDG 17—Partnerships for Goals—through which we can start to identify who the beneficiaries of this system really are.

The stated UN SDG 17 aim is, in part, to:

Enhance global macroeconomic stability, including through policy coordination and policy coherence. [. . .] Enhance the global partnership for sustainable development, complemented by multi-stakeholder partnerships [. . .] to support the achievement of the sustainable development goals in all countries. [. . .] Encourage and promote effective public, public-private and civil society partnerships, building on the experience and resourcing strategies of partnerships.

From this, we can deduce that “multi-stakeholder partnerships” are supposed to work together to achieve “macroeconomic stability” in “all countries.” This will be accomplished by enforcing “policy coordination and policy coherence” constructed from the “knowledge” of “public, public-private and civil society partnerships.” These “partnerships” will deliver the SDGs.

This word-salad requires some untangling, because this is the framework that enables the implementation of every SDG “in all countries.”

Before we do, it is worth noting that the UN often refers to itself and its decisions using grandiose language. Even the most trivial of deliberations are treated as “historic” or “ground breaking,” etc. There is also a lot of fluff to wade through about transparency, accountability, sustainability and so on.

These are just words which require corresponding action in order to have contextual meaning. “Transparency” doesn’t mean much if crucial information is buried in endless reams of impenetrable bureaucratic waffle that isn’t reported to the public by anyone. “Accountability” is an anathema if even national governments lack the authority to exercise oversight over the UN; and when “sustainable” is used to mean “transformative,” it becomes an oxymoron.

Untangling the UN-G3P SDG Word Salad

The UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) commissioned a paper which defines “multi-stakeholder partnerships” as:

[P]artnerships between business, NGOs, Governments, the United Nations and other actors.

These “multi-stakeholder partnerships” are supposedly working to create global “macroeconomic stability” as a prerequisite for the implementation of the SDGs. But, just like the term “intergovernmental organisation,” the meaning of “macroeconomic stability” has also been transformed by the UN and its specialised agencies.

While macroeconomic stability used to mean “full employment and stable economic growth, accompanied by low inflation,” the UN have announced that isn’t what it means today. Economic growth now has to be “smart” in order to meet SDG requirements.

Crucially, fiscal balance—the difference between a government’s revenue and expenditure—must accommodate “sustainable development” by creating “fiscal space.” This effectively disassociates the term “macroeconomic stability” from “real economic activity.”

Climate change is seen, not just as an environmental problem, but as a “serious financial, economic and social problem.” Therefore “fiscal space” must be engineered to finance the “policy coordination and policy coherence” needed to avert the prophesied disaster.

The UN Department for Economic and Social Affairs (UN-DESA) notes that “fiscal space” lacks a precise definition. While some economists define it simply as “the availability of budgetary room that allows a government to provide resources for a desired purpose,” others express “budgetary room” as a calculation based upon a countries debt-to-GDP ratio and “projected” growth.

UN-DESA suggests that “fiscal space” boils down to the estimated—or projected—“debt sustainability gap.” This is defined as “the difference between a country’s current debt level and its estimated sustainable debt level.”

No one knows what events may impact future economic growth. A pandemic or another war in Europe could severely restrict it, or cause a recession. The “debt sustainability gap” is a theoretical concept based upon little more than wishful thinking.

As such, this allows policy makers to adopt a malleable, and relatively arbitrary, interpretation of “fiscal space.” They can borrow to finance sustainable development spending, irrespective of real economic conditions.

The primary objective of fiscal policy used to be to maintain employment and price stability and encourage economic growth through the equitable distribution of wealth and resources. It has been transformed by sustainable development. Now it aims to achieve “sustainable trajectories for revenues, expenditures, and deficits” that emphasise “fiscal space.”

If this necessitates increased taxation and/or borrowing, so be it. Regardless of the impact this has on real economic activity, it’s all fine because, according to the World Bank:

Debt is a critical form of financing for the sustainable development goals.

Spending deficits and increasing debt are not a problem because “failure to achieve sustainable development goals” would be far more unacceptable and would increase debt even further. Any amount of sovereign debt can be heaped upon the taxpayer in order to protect us from the much more dangerous economic disaster that would allegedly befall us if the SDGs aren’t quickly implemented.

In other words, economic, financial and monetary crises will hardly be absent in the world of “sustainable development.” The rationale outlined above will likely be used to justify such crises. This is the model envisioned by the UN and its “multi-stakeholder partners.” For those behind the SDGs, the ends justify the means. Any travesty can be justified as long as it is committed in the name of “sustainability.”

We are faced with a global policy initiative, affecting every corner of our lives, based upon the logical fallacy of circular reasoning. The effective destruction of society is necessary in order to protect us from something that we are told is to be much worse.

Obedience is a virtue because, unless we adhere to the policy demands imposed upon us, and accept the costs, the climate disaster might come to pass.

Armed with this knowledge, it becomes much easier to translate the convoluted UN-G3P word-salad and figure out what the UN actually means by the term “Sustainable Development”:

Governments will tax their populations, increasing deficits and national debt where necessary, to create financial slush funds that private multinational corporations, philanthropic foundations and NGOs can access in order to distribute their SDG compliance-based products, services and policy agendas. The new SDG markets will be protected by government sustainability legislation, which is designed by the same “partners” who profit from and control the new global SDG-based economy.